title: [Statistic] Linear Mixed Model for correlated data categories: [others] tags: [Others, method] excerpt: panel data, linear mixed model

Linear Mixed Model for correlated data

1.Correlated Data

Correlated Data is literally data that samples are correlated with each other. The most famous data type of correlated data is Panel Data. So, before we explore the methods to handle such data, we are going to see first what is Panel Data (or called as longitudinal data or repeated measured data).

Usually, a data set that we can see is either Time-Series Data or Cross-Sectional Data.

Time series data is data gathered from one subject over a certain period. For example, a set of annual lowest temperatures in NY is time series data.

On the contrary, cross-sectional data is data gathered from several subjects at just one point of time. For example, a set of lowest temperatures at 1.1.2015 in America’s major cities is cross sectional data.

That is, time series data is data in which the subject is fixed and cross sectional data is data in which time is fixed.

Panel data is data gathered from several subjects over a certain period. For example, a set of annual lowest temperatures in America’s major cities is cross sectional data.

As we could see, cross sectional data and time series data could be seen as a part of panel data.

Then, why don’t we just throw away time series data or cross sectional data and instead use panel data only?. That is because it is statistically hard to analyze panel data.

A lot of simple statistical methods need strong assumptions. The most famous one of them is iid assumption (identically and independently distributed). However, as you can see from the above data, the max temperatures of NY in 2015 and 2014 are surely correlated with each other, so the assumptions are broken.

Usually, when we take statistical assumptions, we just closed our eye and just ignore it. But in this cases, the assumption is too obviously broken that we cannot ignore it. Therefore, statisticians developed several methods to handle such problems. In this posting, I will introduce such methods mainly focused on modeling.

2. Structure of Linear Mixed Model

Assumptions of Linear Model

The linear model is the most famous statistical model and the father of many statistical methods. However, to apply a linear model to a problem, we have to check the assumptions not broken. Below is said to be the standard assumption of linear regression model.

For linear model $y_i = X_i^t\beta +\epsilon_i$ or $Y = X \beta + \epsilon$

- Lineality - $E(\epsilon_i) = 0$ for all i or $E(\epsilon) = 0$

- Homoscedasticity - $Var(\epsilon_i) = \sigma^2$ for all i or $Cov(\epsilon) = \sigma^2 I$

- No Autocorrelation - $Cov(\epsilon_i,\epsilon_j) =0$ for all $i \neq j$ or $Cov(\epsilon) = \sigma^2 I$

- Independence between independent variables and error term- $X_i \perp \epsilon_i$ for all i

- No Multicollinearity

However, correlated data violates 3th assumption. If the assumption is broken, then we cannot trust the result of the LSE estimator(Gauss-Markov Theorem). So we have to change the assumption $Cov(\epsilon) = \sigma^2 I$ to $Cov(\epsilon) = D$ and under this structure, we could make a credible estimator.

There are three famous methods to make them : Linear Mixed Model, Covariance Pattern Model, and Generalized Estimating Equation. But in this posting, we will see only Linear mixed models.

Mixed model is called “mixed” because it mixes fixed effect and random effect when constructing model. In this cases, we call coefficients of independent variables and intercept as “effect”. Then, “fixed effect” means that these coefficients are constants and “random effect” means that these coefficients are random variables.

For example, in the mixed model $y_i= \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_{i1} + \beta_2 x_{i2} + u_0 + u_1 z_{i1} + \epsilon_i$, fixed effects are $\beta_0,\beta_1,\beta_2$ and random effects are $u_0$ and $u_1$.

The reason that the random effects apply is that it can make structure of covariance of Y. Let’s see how it could be done.

Below model is a generalized form of linear mixed model

$Y = X \beta + Z \alpha + \epsilon$

$\beta :$ Fixed Effect, constant

$\alpha :$ Random Effect, random variable ; assume $\alpha \sim N(0,D)$

$\epsilon :$ error term, random variable ; assume $\epsilon \sim N(0,R)$

This structure is actually one of Bayesian hierarchical regression models. This model equation form can be reprise in probability distribution form

$Y \mid \alpha \sim N(X \beta + Z \alpha ,R)$

$\alpha \sim N(0,D)$

We can not define it as $Y \sim N(X\beta +Z\alpha , R)$ because the distribution contains a random variable. So we have to construct a conditional form like above. This kind of model is called a “conditional model”.

Now, explore further and find $E(Y)$ and $Var(Y)$. It can be derived using the theorem of iterative expectation and theorem of variance decomposition(or, Law of total variance).

$E(y) = E_{\alpha} (E_\epsilon(y \mid \alpha)) = E_{\alpha}(X \beta + Z \alpha) = X \beta$

$Var(y) = E_{\alpha}(Var_\epsilon(y \mid \alpha)) + Var_{\alpha}(E_\epsilon(y \mid \alpha))$

$= E_{\alpha}(R) + Var_\epsilon(X\beta + Z \alpha)$

$= R + Z D Z^t$

So, we can define a structured form of covariance as $R + ZDZ^t$ by using random effects. If we set the random effect adequately, then we could get a reasonable structure of covariance.

Generally, analysts won’t weigh it on random effects because they are some kind of auxiliary variable to capture autocorrelation. But, sometimes, the random effect itself could be the target of the study.

3. Example 1: Random intercept model

By observing the example, we could understand how this structure can work to make covariance.

Let’s consider the medical survey which contains n patients and each patient is examined 3 times. And there are several independent variables X and the result of examination Y. Then we have a model below

Model : $y_{ij} = \beta_1 x_{ij1} + \beta_2 x_{ij2} + u_i + \epsilon_{ij}$ : ith patient’s jth examination result

It is helpful to write down the actual design matrix of the model.

$\quad y \ \quad= \qquad X\beta \qquad \qquad \quad \ \ +\qquad \qquad Z u \quad \qquad \qquad \qquad + \qquad \epsilon$

$\left[\begin{array}{c} y_{11} \\ y_{12} \\ y_{13}\\ y_{21} \\ y_{22} \\ \vdots \\ y_{n3} \end{array}\right] = \left[\begin{array}{cc} x_{111} & x_{112} \\ x_{121} & x_{122} \\ x_{131} & x_{132} \\ x_{211} & x_{212} \\ x_{221} & x_{222} \\ \vdots & \vdots \\ x_{n31} & x_{n32}\end{array}\right] \left[\begin{array}{c} \beta_{1} \\ \beta_{2}\end{array}\right]+\left[\begin{array}{c} 1 & 0 & 0& \cdots & 0\\1 & 0 & 0& \cdots & 0\\1 & 0 & 0& \cdots & 0\\0 & 1 & 0& \cdots & 0\\0 & 1 & 0& \cdots & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots &\vdots &\vdots& \vdots \\ 0&0&0&\cdots&1 \end{array}\right]\left[\begin{array}{c}u_1 \\ u_2 \\ u_3\\ \vdots \\ u_n\end{array}\right] +\qquad \left[\begin{array}{c} \epsilon_{11} \\ \epsilon_{12} \\ \epsilon_{13} \\ \epsilon_{21} \\ \epsilon_{22} \\ \vdots \\ \epsilon_{n3} \end{array}\right]$

$(3n \times 1)$ $(3n \times 2)$ $(2\times 1)$ $(3n \times n)$ $(n \times n)$ $(3n \times 1)$

In this model, we will simplify the pattern of covariance as follows.

$Var(\epsilon) = R = \sigma^2 I$ i.e. $Var(\epsilon_{ij}) = \sigma^2 \quad \forall i,j $

$Var(u) = D = diag(\sigma_i)$ i.e. $Var(u_i) = \sigma_i^2 \quad \forall i$

This is not an overly simplified one but a reasonable one. It saids that the results of one subject can be correlated but the results of two subjects are independent of each other.

This model has expectation and variance as follows.

$E(y_{ij}) = \beta_1 x_{ij1} + \beta_2 x_{ij2}$

- It is the same as a normal linear model, so we could translate it as usual.

$Var(y_{ij}) = \sigma^2 + \sigma_i^2$

- Individual result’s variance is a form of General Variance($\epsilon_{ij}$) + Subject Variance($u_i$)

$Cov(y_{ij},y_{ij}) = \sigma_i^2$

- Covariance of results of same subject is modeled with variance of $u_i$

$Cov(y_{ij}, y_{kl}) = 0 \mbox{ where } i \neq k $

- Covariance of results of different subjects is resulted in 0

Whole covariance matrix is below. Notice that it is block diagonal

$Cov(Y) = \left[\begin{array}{c} \sigma^2 + \sigma_1^2 & \sigma_1^2 & \sigma_1^2 & 0&0& \cdots & 0\\ \sigma_1^2 & \sigma^2 + \sigma_1^2 & \sigma_1^2&0&0& \cdots & 0\\ \sigma_1^2 & \sigma_1^2 & \sigma^2 + \sigma_1^2&0&0& \cdots & 0\\ 0 & 0 & 0& \sigma^2 + \sigma_2^2 & \sigma_{2}^2 & \cdots & 0\\ 0 & 0 & 0& \sigma_2^2 & \sigma^2 + \sigma_2^2 & \cdots & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots &\vdots &\vdots& \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ 0&0&0&0&0&\cdots&\sigma^2 + \sigma_n^2 \end{array}\right]$

Therefore, by applying a random effect in the intercept, we could make a model that correlates with the inner subject.

Detailed provement of the above result is as follows.

pf)

$E(y_{11}) = E(E(y_{11}\mid u_1)) $

$= E(E(\beta_1 x_{111} + \beta_2 x_{112} + u_1 + \epsilon_{11}\mid u_1)) $

$= E(\beta_1 x_{111} + \beta_2 x_{112} + u_1)$

$= \beta_1 x_{111} + \beta_2 x_{112} =X_{11} \beta$

$Var(y_{11}) = E(Var(y_{11} \mid u_1)) + Var(E(y_{11} \mid u_1))$

$= E(Var(\beta_1 x_{111} + \beta_2 x_{112} + u_1 + \epsilon_{11}\mid u_1)) + Var(E(\beta_1 x_{111} + \beta_2 x_{112} + u_1 + \epsilon_{11}\mid u_1))$

$= E( \sigma^2) + Var(\beta_1 x_{111} + \beta_2 x_{112} + u_1 )$

$= \sigma^2 + \sigma_1^2$

$Cov(y_{11}, y_{12}) = E(Cov(y_{11},y_{12} \mid u_1)) + Cov(E(y_{11} \mid u_1) , E(y_{12} \mid u_1))$

$=E(Cov(\beta_1 x_{111} + \beta_2 x_{112} + u_1 + \epsilon_{11},\beta_1 x_{121} + \beta_2 x_{122} + u_1 + \epsilon_{12}\mid u_1)) $

$+ Cov(E(\beta_1 x_{111} + \beta_2 x_{112} + u_1 + \epsilon_{11},\beta_1 x_{121} + \beta_2 x_{122} + u_1 + \epsilon_{12}\mid u_1))$

$= E(Cov(\epsilon_{11} , \epsilon_{12})) + Cov(\beta_1 x_{111} + \beta_2 x_{112} + u_1 ,\beta_1 x_{121} + \beta_2 x_{122} + u_1 )$

$= E(0) + Cov(u_1 ,u_1 ) = \sigma_1^2$

$Cov(y_{11}, y_{21}) = E(Cov(y_{11},y_{21} \mid u_1,u_2)) + Cov(E(y_{11} \mid u_1) , E(y_{21} \mid u_2))$

$=E(Cov(\beta_1 x_{111} + \beta_2 x_{112} + u_1 + \epsilon_{11},\beta_1 x_{211} + \beta_2 x_{212} + u_2 + \epsilon_{21}\mid u_1 , u_2)) $

$+ Cov(E(\beta_1 x_{111} + \beta_2 x_{112} + u_1 + \epsilon_{11},\beta_1 x_{211} + \beta_2 x_{212} + u_2 + \epsilon_{21}\mid u_2))$

$= E(Cov(\epsilon_{11} , \epsilon_{21})) + Cov(\beta_1 x_{111} + \beta_2 x_{112} + u_1 ,\beta_1 x_{211} + \beta_2 x_{212} + u_2 )$

$= E(0) + Cov(u_1 ,u_2 ) = 0$

4. Example 2: Random Coefficient model

Example 1 is the form that the random effects are applied in intercept only like below.

$\left[\begin{array}{c} y_{11} \\ y_{12} \\ y_{13} \\ y_{21} \\ y_{22} \\ \vdots \\ y_{n3} \end{array}\right] = \left[\begin{array}{cc} x_{111} & x_{112} \\ x_{121} & x_{122} \\ x_{131} & x_{132} \\ x_{211} & x_{212} \\ x_{221} & x_{222} \\ \vdots & \vdots \\ x_{n31} & x_{n32}\end{array}\right] \left[\begin{array}{c} \beta_{1} \\ \beta_{2}\end{array}\right]+\left[\begin{array}{c} 1 & 0 & 0& \cdots & 0\\ 1 & 0 & 0& \cdots & 0\\ 1 & 0 & 0& \cdots & 0\\ 0 & 1 & 0& \cdots & 0\\ 0 & 1 & 0& \cdots & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots &\vdots &\vdots& \vdots \\ 0&0&0&\cdots&1 \end{array}\right]\left[\begin{array}{c}u_1 \\ u_2 \\ u_3\\ \vdots \\ u_n\end{array}\right] +\qquad \left[\begin{array}{c} \epsilon_{11} \\ \epsilon_{12} \\ \epsilon_{13}\\ \epsilon_{21} \\ \epsilon_{22} \\ \vdots \\ \epsilon_{n3} \end{array}\right]$

$\left[\begin{array}{c} y_{11} \\ y_{12} \\ y_{13}\\ y_{21} \\ y_{22} \\ \vdots \\ y_{n3} \end{array}\right] = \left[\begin{array}{cc} x_{111} & x_{112} \\ x_{121} & x_{122} \\ x_{131} & x_{132} \\ x_{211} & x_{212} \\ x_{221} & x_{222} \\ \vdots & \vdots \\ x_{n31} & x_{n32}\end{array}\right] \left[\begin{array}{c} \beta_{1} \\ \beta_{2}\end{array}\right]+\left[\begin{array}{c}u_1 \\ u_1 \\ u_1 \\ u_2 \\ u_2 \\ \vdots \\ u_n\end{array}\right] +\qquad \left[\begin{array}{c} \epsilon_{11} \\ \epsilon_{12} \\ \epsilon_{13}\\ \epsilon_{21} \\ \epsilon_{22} \\ \vdots \\ \epsilon_{n3} \end{array}\right]$

In this case, covariances of each 1st and 2nd, 1st and 3rd, 2nd and 3rd are considered the same. This is called sphericity. But it is reasonable to think that the 1st one is more correlated with the 2nd one than the 3rd one. Therefore, it can be seen as an assumption or a constraint. In repeated measures ANOVA, it is an important assumption.

However, mixed models do not have to be stuck to such constraints. If we set a random effect in the coefficients of time, then we could design such a case too.

$\left[\begin{array}{c} y_{11} \\ y_{12} \\ y_{13}\\ y_{21} \\ y_{22} \\ \vdots \\ y_{n3} \end{array}\right] = \left[\begin{array}{cc} x_{111} & x_{112} \\ x_{121} & x_{122} \\ x_{131} & x_{132} \\ x_{211} & x_{212} \\ x_{221} & x_{222} \\ \vdots & \vdots \\ x_{n31} & x_{n32}\end{array}\right] \left[\begin{array}{c} \beta_{1} \\ \beta_{2}\end{array}\right]+\left[\begin{array}{c} 1 & 0 & 0& \cdots & 0\\ 1 & 0 & 0& \cdots & 0\\ 1 & 0 & 0& \cdots & 0\\ 0 & 1 & 0& \cdots & 0\\ 0 & 1 & 0& \cdots & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots &\vdots &\vdots& \vdots \\ 0&0&0&\cdots&1 \end{array}\right]\left[\begin{array}{c}u_1 \\ u_2 \\ u_3\\ \vdots \\ u_n\end{array}\right] + \left[\begin{array}{c} 1 & 0 & 0& \cdots & 0\\ 2 & 0 & 0& \cdots & 0\\ 3 & 0 & 0& \cdots & 0\\ 0 & 1 & 0& \cdots & 0\\ 0 & 2 & 0& \cdots & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots &\vdots &\vdots& \vdots \\ 0&0&0&\cdots&3 \end{array}\right] \left[ \begin{array}{c} v_1 \\ v_2 \\ \vdots \\ v_n \end{array}\right]+ \qquad \left[\begin{array}{c} \epsilon_{11} \\ \epsilon_{12} \\ \epsilon_{13}\\ \epsilon_{21} \\ \epsilon_{22} \\ \vdots \\ \epsilon_{n3} \end{array}\right]$

In model form, $y_{ij} =\beta_1 x_{ij1}+ \beta_2 x_{ij2} +u_i + v_{ij} \mbox{T}{ij} + \epsilon{ij} $

We again assume $v_{ij} \sim N(0, \tau_i^2)$.

In this case, we could make covariance structured as follows.

$E(y_{ij}) = \beta_1 x_{ij1} + \beta_2 x_{ij2}$

- It is the same as a normal linear model, so we could translate it as usual.

$Var(y_{ij}) = \sigma^2 + \sigma_i^2 + \mbox{T}_{ij}^2 \tau_i^2$

- Individual variance is decomposed with General Variance($\epsilon_{ij}$) + Subject Variance($u_i$) + Time Variance($v_i T_{ij}$)

$Cov(y_{ij},y_{ik}) = \sigma_i^2 + \mbox{T}{ij}\mbox{T}{ik} \tau_i^2 $

- Covariance of results of same subject is decomposed with Subject Variance($u_i$) + Covariance weighted in time($v_{ij}$)

$Cov(y_{ij}, y_{lk}) = 0 \mbox{ where } i \neq l$

- Covariance of results of different subjects is 0

Below is the matrix form of covariance of the model.

$Cov(Y) = \left[\begin{array}{c} \sigma^2 + \sigma_1^2 +T_{11}^2\tau_1^2& \sigma_1^2 +T_{11}T_{12}\tau_1^2& \sigma_1^2 +T_{11}T_{13}\tau_1^2& 0&0& \cdots & 0\\ \sigma_1^2 +T_{11}T_{12}\tau_1^2& \sigma^2 + \sigma_1^2 +T_{12}^2\tau_1^2& \sigma_1^2+T_{12}T_{13}\tau_1^2&0&0& \cdots & 0\\ \sigma_1^2 +T_{11}T_{13}\tau_1^2& \sigma_1^2 +T_{12}T_{13}\tau_1^2& \sigma^2 + \sigma_1^2 +T_{13}^2\tau_1^2&0&0& \cdots & 0\\ 0 & 0 & 0& \sigma^2 + \sigma_2^2 +T_{21}^2\tau_2^2& \sigma_{2}^2 +T_{21}T_{22}\tau_2^2& \cdots & 0\\ 0 & 0 & 0& \sigma_2^2 \sigma_{2}^2 +T_{21}T_{22}\tau_2^2& \sigma^2 + \sigma_2^2 +T_{22}^2\tau_2^2& \cdots & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots &\vdots &\vdots& \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ 0&0&0&0&0&\cdots&\sigma^2 + \sigma_n^2 +T_{n3}^2\tau_n^2 \end{array}\right]$

In this time, the covariance between different times is proportional with time of examination. Therefore, we could design such variance too.

Detailed provement of the above result is as follows.

$E(y_{ij}) = E(E(y_{ij} \mid u_i))$

$= E(E(E(y_{ij}\mid u_i,v_i)))$

$= E(E(E(\beta_1 x_{ij1}+ \beta_2 x_{ij2} + u_i+v_iT_{ij} +\epsilon_{ij} \mid u_i , v_i)))$

$= E(E(\beta_1 x_{ij1}+ \beta_2 x_{ij2} + u_i+v_i T_{ij} \mid u_i,v_i))$

$= E(\beta_1 x_{ij1} + \beta_2 x_{ij2} + u_i\mid u_i)$

$= \beta_1 x_{ij1}+ \beta_2 x_{ij2}$

$Cov(y_{ij},y_{ik}) = Cov(E(y_{ij}\mid u_i),E(y_{ik}\mid u_i))+E(Cov(y_{ij},y_{ik} \mid u_i))$

1) $E(y_{ij} \mid u_i) = E(E(y_{ij} \mid u_i , v_i))$

$=E(\beta_1 x_{ij1}+ \beta_2 x_{ij2} + u_i+v_iT_{ij} \mid u_i , v_i)$

$=\beta_1 x_{ij1}+ \beta_2 x_{ij2} + u_i$

2) $Cov(E(y_{ij}\mid u_i),E(y_{ik}\mid u_i)) = Cov(\beta_1 x_{ij1}+ \beta_2 x_{ij2} + u_i,\beta_1 x_{ij1}+ \beta_2 x_{ij2} + u_i)$

$= Cov(u_i,u_i) = \sigma_i^2$

3) $Cov(y_{ij},y_{ik} \mid u_i) = Cov(E(y_{ij} \mid v_i), E(y_{ik} \mid v_i) \mid u_i)+ E(Cov(y_{ij},y_{ik} \mid v_i) \mid u_i)$

$= Cov(\beta_1 x_{ij1}+ \beta_2 x_{ij2} + u_i+v_iT_{ij},\beta_1 x_{ij1}+ \beta_2 x_{ij2} + u_i+v_iT_{ik} \mid u_i) $

$ +E(Cov(\beta_1 x_{ij1}+ \beta_2 x_{ij2} + u_i+v_iT_{ij} + \epsilon_{ij},\beta_1 x_{ij1}+ \beta_2 x_{ij2} + u_i+v_iT_{ij}+\epsilon_{ik} \mid v_i)\mid u_i)$

$= Cov(v_i T_{ij},v_i T_{ik} \mid u_i) + E(Cov(\epsilon_{ij},\epsilon_{ik} \mid v_i) \mid u_i)$

$= T_{ij}T_{ik} \tau_i^2 + 0$

$\therefore Cov(y_{ij},y_{ik}) = \sigma_i^2 + T_{ij}T_{ik}\tau_i^2$

$Var(y_{ij}) = Cov(y_{ij},y_{ik}) = \sigma_i^2 + T_{ij}^2 \tau_i^2$

$Cov(y_{ij},y_{lk}) = 0$ (skip…. I’m tired..)

These examples are the most basic form of mixed model. We could apply such forms to various problems.

For example, we could add different random effect to model,

ex) the value of k-th observing result of i-th patient with j-th method.

$y_{ijk} = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_{ijk } + u_{i} + v_{j} + \epsilon_{ijk}$

could analyze a independent variable with fixed effect and random effect at the same time,

ex) the value of k-th observing the result of i-th patient.

$y_{ij} = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_{ij} + u_{i} + v_{i}x_{ij} + \epsilon_{ij}$

In this case, the coefficient of $x_{ij}$ is $(\beta_1+ v_i)$and it means that the effect of $x_{ij}$($\beta_1$) can be differed in subjects with $v_i$.

or could add random effects to the interaction term.

ex)the value of k-th observing the result of i-th patient with the j-th method.

$y_{ijk} = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_{ijk } + u_{i} + v_{j} + \tau_{ij} + \epsilon_{ijk}$

We can construct the correlated relation with the i-th patient and j-th method.

5. Analysis with R

We could design such a mixed model in R by using the package “lme4”.

library(lme4)

lmer(formula, data = NULL, REML = TRUE, control = lmerControl(),

start = NULL, verbose = 0L, subset, weights, na.action,

offset, contrasts = NULL, devFunOnly = FALSE, ...)

# Form of formula

y ~ x1 + x2 + (1|z1) + (1|z2) + (t|z1) + (x1|z1) + (1|z1:z2)

# y: dependent variable

# x1 + x2: give fixed effect in x1,x2.

# (1|z1) + (1|z2): give random intercept effect in z1 and z2.

# (t|z1): give random coefficient effect to t with z1

# (x1|z1) : give random coefficient effect to x1 with z1

# (1|z1:z2) : give random intercept effect to interaction of z1 and z2

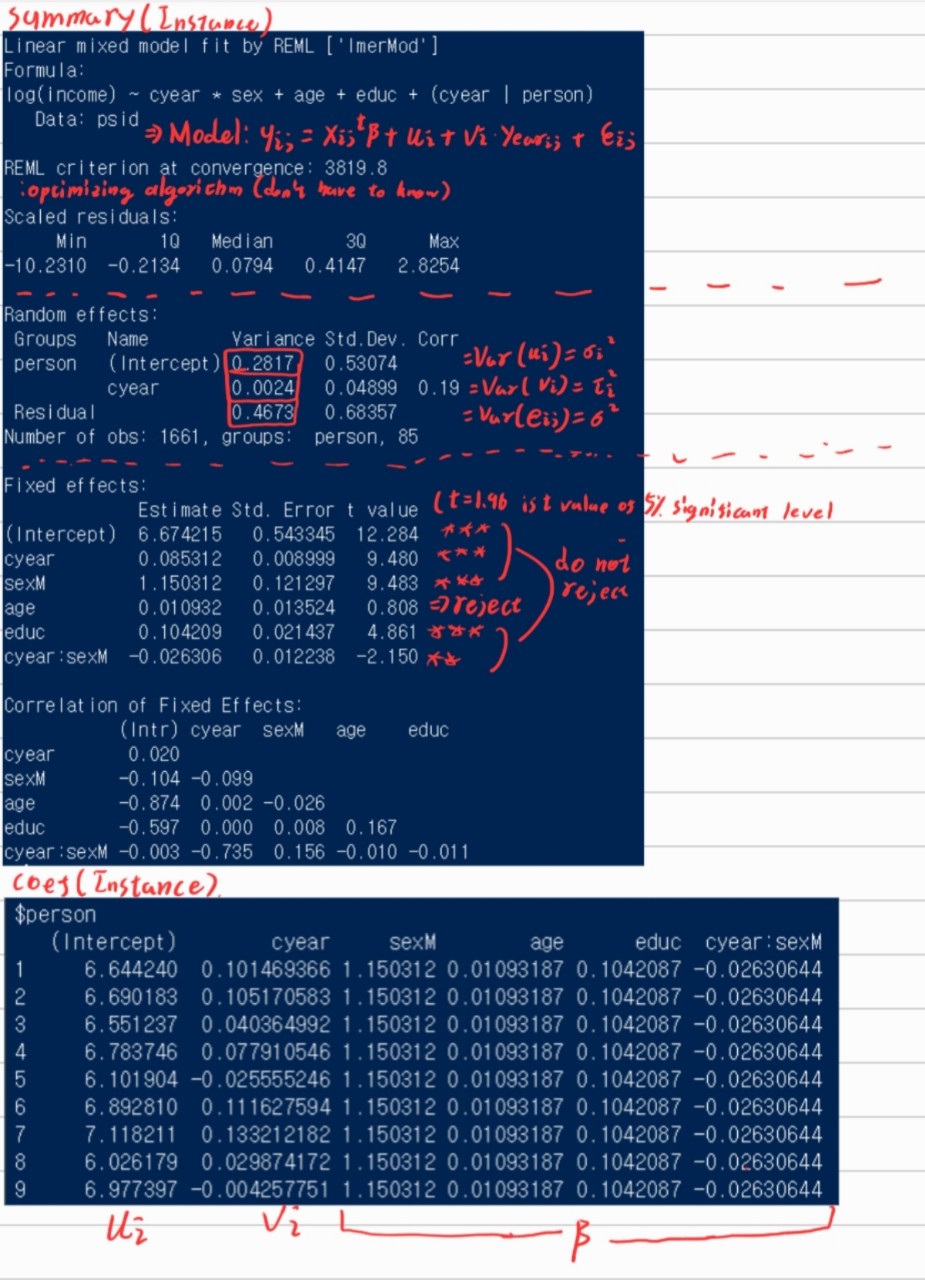

And we could interpret the results as follows.

6. Additional Strength

- It could be used Generalized linear model too.

Generalized linear model is a generalized version of linear model which has the following form.

$Y_i \sim exponential family$

$g(E(Y_i)) = X_i^t\beta$

We call g(.) as a link function. With proper link function, we could design various models.

For example, logistic regression has the form as follows.

$y_i \sim Bernoulli (\theta_i)$

$\log \frac{\theta_i}{1-\theta_i} = X_i^t \beta \iff \theta_i = (1+exp(-X_i^t \beta))^{-1}$

Even in this case, we could add random effects as follows.

$y_i \mid \theta_i \sim Bernoulli (\theta_i)$

$\theta_i\mid \alpha_i = (1+exp(-X_i^t \beta - Z_i^t \alpha_i))^{-1}$

$\alpha_i \sim N(0,\sigma_i^2)$

Moreover, mixed models have the strength to handle missing data easily and can make personalized predictions but I’m not gonna say it deeper.